Link to Rock and Ice #212

Tangled Border: Partnership and Adventure in the Ak Su, pages 37-43

Tangled Borders

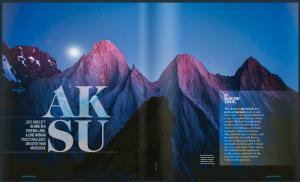

Partnership and Adventure in the Ak Su, Kyrgyzstan

By Madaleine Sorkin

The trail forked again at a shady grove of trees and I looked around, at first hopeful and then in frustration, for one of Nik’s arrows drawn in the sand. The junction was too large and vague to know where he may have drawn it. My throat and stomach clenched again and I closed my eyes to tears. This was still really happening I was still alone, in Kyrgyzstan of all places, and we hadn’t even climbed yet. The top of a rocky peak had come into view and I guessed the direction of the Ak Su valley, up a steepening valley of short grasses, shrubs and rocky soil. The rising trail baked under the late afternoon sun and a bright blue sky. I lingered under the grove reluctant to leave the companionship of the river. A small side spring into it had provided the only clearer water I’d had all day and its constant sound quieted my dark thoughts. One foot in front of the other, I repeated to myself but I felt heavier with each step. A headache split my right eye and my neck stiffened around a pain shooting up into my head. Where are they? Have they gone ahead to base camp? Surely someone will come back for me once they unload.

Livestock paths muddled the trail and I wove around trying to stay on the contour. I’d been sick for the night before our pre-dawn start, and last saw Nik and the porters mid-morning, six hours ago. After another hour, my legs buckled and I slumped down in the dirt. I considered the possibility that I might not find them before nightfall. The rocky peak was now in fuller view and I felt better about my general direction but exhausted and the valley continued to rise. I spotted a trail on the other side of the river, now far below, and my stomach tightened again. Maybe I’m on the wrong side. Waves of rage and disbelief engulfed me. How is this still happening? Where the hell is Nik?

I had a jacket and a few sips of water left. Keep moving while it’s still light.

[ls]

I know what had drawn me to Nik Berry as a person—he listens to you with wide-open eyes and has an easy, good-natured manner. In climbing, I respected his motivation, confidence and dedication to trying hard. Nik embraces 4 a.m. starts like the words that always come into my mind—a joyful robot. We’d hit it off in March, while working at a Red Rocks climbing event for our mutual sponsor Outdoor Research, when we squeezed in climbing whenever possible, early or late. We simul-climbed by headlamp, practiced our dance moves at cold belays, and unlocked sequences of difficult pitches.

When I rose yet again in the dark, climbing in Red Rocks for the fourth day in a row, I said to my girlfriend, “I think I’ve found someone more motivated than I am for a change.”

She just said, “It’s about time.”

Nik and I had each set our sights on Yosemite, and decided to climb a free route together on El Capitan. He arrived in the Valley before I did, free climbing The Prophet (VI, 5.13d R) and then hiking other climbers’ loads up Half Dome and El Cap for extra money before we two attempted El Corazon (VI 5.13b). On El Corazon he weathered my initial (and, I’m afraid, not entirely atypical) negativity when I previewed and first tried the top cruxes:

“I can’t do it,” I said. I also said, serially:

“I don’t get it.”

“My shoulder hurts.”

And: “That sequence won’t work/is too powerful for me.”

Nik was patient and said straightforward and odd but comical things like, “Too bad you don’t have a penis.” I saw a little brother in him, someone I could talk shit to and whose encouragement when so effusive when I was leading that my attention to trying hard increased. On run-out, and potentially dangerous sections of climbing, I learned to take his laughter as a sign that things were particularly dire. I wanted to learn to face my death smiling like I imagined he would one day.

You might think a guy in his mid-20s (Nik is 26) would be more likely to climb big projects with another young male rather than a 30-year-old woman—but we both like to bite off as big a goal as we think we can possibly chew and our awkward personalities/odd-ball natures felt largely compatible to me. I played into the big sister role with Nik and he seemed to appreciate that as well as my ambition and technical capability. Nik is such a strong climber—ridiculously cool-headed and durable—that I questioned my value in the partnership, because I was accustomed to bringing those same strengths to other partnerships. On El Corazon I felt worthy when I was able to unlock some crux sequences for both of us and I began to open to what I could offer and learn.

Nik didn’t need as much rest as I did, so on El Corazon I either had to keep up or ask him to slow down, and accepting a lead on the route was more a choice than a necessity. On our fourth day on El Corazon, the A5 traverse was my final [difficult] lead and I was solid.

Nik followed and I laughed as he whined in imitation [of my previous attempts at leading the traverse], “This is hard. I’m just gonna think negative thoughts.” At the anchor, he congratulated me with typical generosity: “That was sick. You remembered how to try hard.”

[ls]

I wanted to experience a mountain culture in Central Asia, and after a friend’s report from the previous season, became drawn to Kyrgyzstan’s stellar weather, scant snow, 3,000-foot walls and 4,500-foot ridgelines. Most of my big trips have been with partners after developing a long history of supporting one another’s highs and lows. I often felt a greater accountability in my partnerships with women, and thus the dynamics were all the more supportive as we helped each other push ourselves. While I still often seek out climbing with women, this year I was focused on pushing my climbing performance, and simply finding motivated partners whom I got along with well. In the Spring, I’d teamed up with a 23-yr old young gun, Brad Gobrite, and freed the Hallucinogen Wall (VI 5.13R) and enjoyed reconnecting with youthful enthusiasm that believes anything is possible.

I asked Nik if he’d be interested in freeing big walls the Karavshin region of Kyrgyzstan, we secured funding, and suddenly only five weeks remained before departure. Nik had traveled little outside of North America, and the pre-trip planning hurdles I shared with him were often met with the joke, “Why don’t we just go to the Bugaboos? I felt responsible for the logistical success of the trip and thus a bit protective of our organization from travel to obtaining area information to permits to hiring porters and base camp cooks. In truth I wanted Nik to share the planning responsibility but I wanted him to know what to do without telling him. I settled for requesting assistance on specific tasks and told myself that this big-sister leader role was a new growth area for me.

But I wanted an adventure and told myself that Nik did as well, even when he asked whether the hassles of getting halfway across the world with 400 pounds of gear “maybe” to go rock climbing were worth it.

I was confident in Nik’s and my ability to climb together, however found myself lecturing him about what it meant to climb in remote areas and to travel internationally.

“If we don’t have it, there’s no getting it,” I said. “We need to remember every necessary item. No popping back into town for an antibiotic.”

Nik and I hadn’t climbed in any isolated region together. Our risk thresholds had seemed close enough on El Cap, but overall I was more conservative, so I bugged him [chronically] about things like bringing a helmet.

Texting was our main mode of communication and in our final days of packing, messages such as, “Will you get more 3/8 bolts?” or “How much does your sleeping bag weigh?” zinged back and forth. The night before our flight, I sent Nik a text.

“We’re going to freaking Kyrgyzstan!!”

“Where the hell is that?” he responded. “Have fun out there.”

“Yeah, have you even looked at a map?” I asked.

“That’s what a pilot is for, silly,” he countered.

I found Nik at JFK airport, already $600 deep in excess baggage fees. I was relieved just by the sight of him: Now we were on the adventure together. We flew to Bishtek and, while waiting for lost bags to arrive, adjusted to the 12-hour time difference and explored a capital of bleak Soviet Bloc architecture: uniform, blocky gray concrete. Mostly, we sampled bazaar foods—farmers’ cheese, salty pickled cabbage and runny kefir yogurt—and tried not to get mugged. I laughed as Nik’s guileless gaze invited the attentions of peddler after peddler, but was dogmatic when he seemed too carefree.

“You can’t just leave your bags over there!” I scolded.

“I’m watching them,” he protested, but he retrieved the bags.

[ls]

Five days after our arrival, my gut unraveled, probably from the effects of bazaar food sitting out under a 100-degree sun.

The people from the guide service we’d hired had told us little of getting to base camp except that they’d arranged donkeys and porters for the day-and-a-half walk. After a short flight from Bishkek to the town of Batken, then a three-hour drive in a hired car past the Tajik border point of Vorukh, where the passable road ends, we reached the trailhead, stopping with our driver at a house beside the river. In the evening two Tajik porters arrived and began to load our bags onto the donkeys. I vomited and then tried to convey with gestures that I wasn’t fit to begin this evening. The older of the two porters looked disappointed but nodded as I pointed to my watch and suggested 5 a.m. “Ak Su,” he repeated, and I realized I’d agreed to complete the 30-mile walk in a day.

As others slept, I endured dizzying cycles of illness, stumbling around outside under a clear starry sky. At first light, I watched as the porters loaded our 400 pounds of equipment onto four donkeys—who gave little protest except to shit as the weighty contraptions were cinched across their bellies. In solidarity, my hollow stomach churned acid.

The porters, donkeys, Nik and I began at 5 a.m. A desert landscape stretched before us and I had less than a liter of water. The river was thick with sediment. Nik gave me most of his remaining water and said he would use our water-treatment pills, which he carried in his daypack. I shuffled beside the river along a trail of sand and rocks, determined to keep moving. After a late-morning break, Nik and the porters pulled ahead, out of sight. As the sun rose higher, my legs and arms burned dry and I hid under the brim of my hat.

Two hours passed. Where are you, Nik? Where are the porters and donkeys? I glanced at my watch and groaned. 1 p.m. and many hot hours ahead. Around a twist in the trail, a full water bottle sat squarely on a rock. I assumed it was from Nik and was at once thankful and cautious—the water was deep brown and the last time I saw Nik treat water he’d used half the recommended dose.

Drawn by the shade of a shrub, I lay down and curled up around my pack. Had pride kept me from asking Nik to walk with me? Why couldn’t he get it like my other partners would have?

I awoke to the sound of hooves and laughter, and sat up to greet a man with donkeys.

“Ruski? Kyrgeez?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. “Ak Su.”

I pointed up river, and he nodded, gesturing to himself and saying, “Lailak.” I took out a map with a 6-inch quadrant of this Karavshin region. Lailak appeared to be further up river than the turn-off for the Ak-Su valley. He extended an open hand. I stood up into the sun and handed over my pack.

“Rahmat,” I said.

He repeated a word until I mounted the donkey, already laden with bags. The man asked about water and I fished out the silty bottle. He shook his head and emptied it onto the ground. The scene was slow motion and captivating.

When the donkey grew tired and began to lag, I dismounted. My thirst returned with a vengeance. I dragged behind my new friend, then saw another patch of shade over the river by a rickety wooden bridge. I found a clear stream feeding into the river, filled my bottles, drank down cold untreated water, and caught up to find the man waiting beside a dilapidated stone-mud structure. He sat on a rock and gestured for me to join him. Sun-bleached animal skulls were placed along a few of the walls, and he prayed aloud and I sat quietly, trying to open myself to the moment.

Resuming the walk, we soon came to an intersection with one trail leading left off the main river. The man continued but I was fairly certain that this was the turn off toward the Ak Su valley. I stopped and pointed.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

He nodded and gave me my pack. I thanked him, and handed him a little money.

At 3:30 p.m. I turned toward the Ak-Su trail [tk what Ak Su trail? I don’t understand the Q] and saw a heart and arrow drawn in the sand. Thank you, Nik.

By early evening, I began to consider my options for spending the night out. I paused at roofless shepherd’s hut, but I continued walking, telling myself I could return to it if I had to.

At nightfall (8pm?) I saw people and a house, livestock drawn close for the night. A few men and a boy stood together, each with a staff in hand.

“Salam-alay-kem,” I said as I approached. From behind the men, a smiling girl peeked out.

“Have you seen two Tajik men and one American?” My fingers walked across my hand and I pointed to myself when I said American.

“Yes,” the youngest of the men said in English.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

“Yes, Ak Su.”

“How long?” I asked, really pushing his English. I pointed to my watch and made numbers with my fingers. One? Two hours? The man held up three fingers. I shook my head and looked at the ground. Then he brought his hands together and I understood that I was invited to stay.

A woman came out of the house and invited me inside. On a small blanket in the middle of the floor sat a pot of chai and plate of naan. The woman—whose name, I learned, was Rita—poured chai and broke bread for me and then rose to tend to a large pot over a fire. The rest of the family entered and we sat in a circle: four men, two women, two kids, a baby. The father poured chai and broke bread for the group. Bowls of borscht were brought out. We dipped naan in the clear fatty broth of cabbage, potato, carrot and a piece of mutton. The women cleared food away, and Rita unrolled blankets from the edges of the room and pointed to mine. I lay down and tears filled my eyes. I was safe, fed, cared for.

When I rose in the morning, my legs were shaky but I felt both restored and blessedly fortunate to have found this beautiful family. The sun was high and neither Nik nor the porters had returned for me. Partially in disbelief, I lingered through the morning.

After breakfast, I told the family I was leaving for Ak Su. I gave Rita money. She shook her head, but I pressed and she took it to her husband; they seemed pleased. The boy and girl walked with me up the trail from their house. At an intersection, the boy pointed straight ahead and said, “Ak Su.”

En route, I was stopped at a military outpost, encircled [tk is that OK] by a group of armed young men as I stood before them, produced my passport, and tried to answer their questions. Leaving there, I soon met our porters, returning empty-handed from the Ak Su base camp and nodding that Nik and the bags were up river yet. By mid-afternoon I smelled fire and dung. A shepherd emerged from a bivy cave and led me over to Nik, who sat up in his sleeping bag under another rock.

“Hi,” I said. Emotions welled up as I found a place to sit and at first I didn’t hear what he said.

“Are you OK? I’ve been so worried.”

“Well, I made it,” I said, wondering what the hell he was doing napping instead of looking for me.

Nik described his surprise and dismay when the porters kept going and picked up speed without me. His only options had been either to wait or to follow and keep an eye on our bags, which contained our money and his passport as well as all our gear, and he kept expecting that the porters would eventually stop. When it was clear to him that they weren’t waiting, he felt trapped—too far away to check on me while still being able to catch up with the men. Before nightfall Nik asked the porters to break camp, only a mile from the intended Ak Su base camp, in hopes that I would find them. He couldn’t sleep. In the morning the porters packed up and kept going to base camp, and he followed.

I listened to his story, nodded and tried to understand. Nik said he would never leave a partner again under any circumstance. I wondered how my own determination and pride as an athlete might have contributed to the situation. Mostly I didn’t want to feel anything, and needed sleep.

I just said, “This bivy sucks.”

“Really?”

He was surprised that I didn’t see its resemblance to the bivy cave where we’d stayed on top of El Cap, but I just wanted to find fault.

“There’s nowhere for me to sleep,” I said irritably.

Nik dug out a flatter spot for me under our “Salathé” cave. I crawled into my bag and woke in the evening, when two shepherds—brothers who lived in the area from May to September—invited us for dinner.

Stepping out from the cave, I took in the landscape for the first time. Our camp was dry, rocky earth peppered with shrubby trees with few flat spots for a tent. Up valley was the snowy, jagged peak Ptitsa that shared a border with Tajikistan. The river poured down towards us and on either side massive granite formations rose up from steep hillsides of scree and then larger talus. I knew the formations from a computer screen, ridges and walls featured with cracks and blank faces. Now staring at the peaks, my mind kept trying to underestimate the distance between myself and the summits.

[ls]

Perestroika means overcoming stagnation and this internationally known route was a fitting first climb after the approach fiasco. Nik and I shared leads up its 25 pitches, starting with a 1,000-foot splitter crack. I took a 5.11+ flaring bulge, and Nik led the last crux, a 5.12- thin corner. Cold and shivering, I turned us around 500 feet before the summit, with Nik reluctant but conceding. He just zipped up his jacket collar and said, in validation, “Well, at least it’s starting to snow.”

After a day’s rest we hiked back up the 1,000-foot talus to the Russian Tower with static ropes and aid gear to check out the Russian Shield on the main steep face. My intestinal distress had returned and I hiked painfully slowly, avoiding eye contact with Nik. By the second pitch, it was clear that this route was a grander undertaking than our 20 bolts, hand drill and psych level were going to muster. We retreated. That evening, I begin taking antibiotics and in the middle of the night, hurrying out to relieve myself, I managed to roll my ankle. As tears gathered in my eyes, I congratulated myself on reaching a new level in being perennially pathetic.

The next day we decided to prioritize my recovery and hike to our supplier’s main camp in the adjacent Kara Su Valley, a 3-hour walk away in my pathetic state. We arrived to a busy scene in the Kara Su. Stand-up dome tents, crates of food, grazing cows and people filled a verdant green meadow with a clear stream running through it. Between the Russian climbing teams, Japanese trekkers, a British group, the German man in his speedo, the Russian cooks and Kyrgyz shepards, I lost count after 30-people.

Victor, our cook, greeted us and assured me that a little little vodka can cure anything. I curled up in our tent and Nik brought tea and a plate of plain rice. For a couple days, we lazed around in the meadow between feeding times and I fondly named our plush camp “Kara Kush.” And as hoped, the antibiotics eradicate every living thing in my gut and our two American friends, Josh Finkelstein and Pete Fasoldt, who have been climbing in the region, returned from a 3-day traverse of the formations dividing the AK Su and Kara Su valleys (Pk 4810, 1000 Y.O.R.C, and Pk Kotina). A “little, little” celebratory vodka is drunk. Soon Nik and I were restless to return to the solitude and rising granite of the Ak Su and bounced with excitement as Victor packed us off with fresh vegetable, grains, sausages, cheese and candy.

Upon our return to our Salathe bivy cave we find that the shepherd Jappar has left Nik a traditional Kyrgyz felt hat as a gift. Nik donned the tall white and thoroughly impractical accessory proudly as he built a fire and cooked with our borrowed Jappar’s cast-iron wok at our Salathé home. We discussed our next objective and Nik asked if I was fit to climb. He added, “If climbing means only doing things in the sun so that you’re not cold, that’s fine.” Nik’s concern felt genuine, and I proclaimed that my general psych level was high and while my ankle was swollen and discolored I assured him that it was manageable.

With binoculars we scoped out La Fiamma, an A3 Italian line just right of Perestroika, and the next day we climbed back up the shoulder of the Russian Tower to the notch below the Perestroika splitter. Deciding to see how far we could get that day, we stretched a 70-meter pitch up Perestroika to an anchor. From there I traversed right into La Fiamma territory, led a runout moderate slab into a shallow corner, and looked up at a snaking seam with a pin hammered into the bottom. Our hammer and set of pins sat back with Nik at the belay.

I yelled down, “I’ll just give it a go with what I have.” The placements got smaller and the climbing harder, up to 5.12-, but the rock was clean and solid. I read a way up the flaring finger grooves, foot edges and smears, Nik cheered and I completed the pitch with a satisfied whoop.

The next two pitches were more moderate, 5.10 climbing on solid rock, and we had just enough rope to rappel and fix most of the route back down to the ground. After a 12-hour day, we returned to base camp with plans to push for the summit in the morning.

We began in harmony at 4 a.m., music blaring from the speakers and water boiling. We jugged back up to our high point, Nik’s lead. Soon he was 20 feet off the belay, making insecure moves with only a marginal, tiny TCU between him and the belay. He reached and clipped a quarter-inch bolt, and I relaxed, sort of. He chuckled. Thumb pressing and insecure foot smears allowed him to move left, and he clipped another quarter-inch bolt. The final crux move ended with a sideways downward lunge to a flat jug. Solid marbled rock through a bulge completed this run-out 5.12c.

A dihedral rose above us, and to avoid placing bolts Nik built an awkward belay on a crumbly ledge midway up it. I began a difficult section, struggling to find satisfactory gear, and climbed up and down several times, unwilling to commit to a move into a thin and wet corner. I bitched and said Nik should take over the pitch (which would turn out to be 5.12-), but I didn’t come down.

Eventually I found enough gear to keep me off the ledge. I committed and found the climbing physical and insecure as I largely avoided the wet finger locks and relied on stemming. I shouted which helped me focus on trying hard and Nik cheered.

We merged with Perestroika from here, right where we had bailed the previous week. The temps were chilly but tolerable and this time I, too, wanted the summit. Five hundred feet of moderate splitters and corners led us to the top. We scrambled up summit choss and took in a sky of purples and pinks in the fading light, the FFA of the route behind us.

“That was a once-in-a-lifetime,” Nik said. “Anything else here is bonus.”

Our team morale was still high when we returned to camp after midnight.

After two rest days we racked up for a king line: Sugar Daddy (VI 5.11+), a ridgeline up the 4,507-meter Peak One Thousand Years of Russian Christianity. A splitter headwall proudly guarded the summit. We’d heard from Russians in the Kara Su that the route probably hadn’t been climbed in a day. We strategized for a hugely aerobic effort with roughly 5,000 feet of vertical gain and an unknown descent, and scoped a descent down the Northwest Ridge, a popular 5.10 that we’d heard can take 12 hours to rap.

The alarm sounded at 3:30 a.m. We hadn’t been to the base of the route, and so after hiking uphill for an hour we were as high as we could go in the dark, and waited for the sun. At the base, Nik considered his helmet before stuffing it back in his pack. Done with nagging, I said nothing.

In two hours, we simuled up the initial section and gained the lower-angle part of the ridge. We un-roped and straddled, scooted, huffed and puffed up it, and after about 1000 feet roped up again. The third, steeper section of the ridge took the longest, with inobvious route finding and technical cruxes. Nik was the hero, forging all the way through this block, dragging the entire rope behind him, and I simply cleaned the occasional cam. We topped out at 5 p.m., 10 hours after we began at the base, and hung out for 45 minutes on top, soaking up the sun before summoning the fortitude to return to the shade.

I volunteered to lead all the rappels. The pulls went smoothly, pitch by pitch, and we settled into a routine. While we still had light I tried to keep a sense of the general direction we wanted to head. By less than halfway down, I finished the last of my food and Nik unhesitatingly gave me some of his.

By 2 a.m. the situation had deteriorated. We’d been off the established rappels since before midnight and were just trying to get down by any safe means. Out of rappel cord, I cut into our lead rope, slinging flakes to descend. As I rapped into a cold small alcove and ledge, the slab below me dropped off into darkness. It was wet and I couldn’t find anything to anchor. I lowered farther. Cold water ran down the rope, a crack opened up into a chimney and I reached the end of the ropes without finding any anchor. I returned to the stance and searched again. My foot slipped and my hand splatted into icy water. Nik was 100 feet up at our last anchor.

“There’s nothing to sling!” I yelled.

“Isn’t there anything? Leave whatever. Cams, Stoppers… I don’t care.”

“I don’t know what to do!”

“Just do something!”

I slung a large rock, using a lot of our rope. After a few more rappels we were walking and Nik was hopeful enough to take off his harness. But soon a new dark abyss opened below our feet, and we began slinging and lowering yet again.

After rappelling from a slung rock down over a broken, overhanging amphitheater, I re-ascended the rope and insisted we stop until daylight. I was too tired to move, and stayed attached to the anchor, half sleeping between the cold and sliding and righting myself on the hillside.

When I awoke it was light and I was alone.

“Nik?” I shouted.

Nothing. I untangled myself from the rope and sprang to my feet.

“Nik!” I screamed. Nothing. “What the fuck!?”

My heart was racing. I began to run up the hill. Then I saw him, a mere 10 feet above, passed out on a flat spot of dirt and oblivious to my cries. He’d been there all along.

Madaleine Sorkin of Boulder has made several first and early ascents of 5.12/5.13 Grade VI walls, often in female teams. She recently earned a Master’s degree in Environmental and Land Use at the University of Colorado Denver. She and Nik Berry of Salt Lake climbed 4 routes during their trip to the Karavsdhin Region of Krygyzstan.

• La Fiamma (VI 5.12c R), Pik Slesova (Russian Tower 4240 m). Completed the first free ascent of the Italian aid line rated A3. Completed ground up, onsight with Nik Berry. Climbed over 1 ½ days.

• SugarDaddy, Pik 1000 Years of Russian Christianity(4507 m). Completed first single day ascent of 1500 m line (VI 5.11+).

• Perestroika (VI 5.12-), Pik Slesova

• The Alperin (V 5.10) Pk Asan

Tangled Borders

Partnership and Adventure in the Ak Su, Kyrgyzstan

By Madaleine Sorkin

The trail forked again at a shady grove of trees and I looked around, at first hopeful and then in frustration, for one of Nik’s arrows drawn in the sand. The junction was too large and vague to know where he may have drawn it. My throat and stomach clenched again and I closed my eyes to tears. This was still really happening I was still alone, in Kyrgyzstan of all places, and we hadn’t even climbed yet. The top of a rocky peak had come into view and I guessed the direction of the Ak Su valley, up a steepening valley of short grasses, shrubs and rocky soil. The rising trail baked under the late afternoon sun and a bright blue sky. I lingered under the grove reluctant to leave the companionship of the river. A small side spring into it had provided the only clearer water I’d had all day and its constant sound quieted my dark thoughts. One foot in front of the other, I repeated to myself but I felt heavier with each step. A headache split my right eye and my neck stiffened around a pain shooting up into my head. Where are they? Have they gone ahead to base camp? Surely someone will come back for me once they unload.

Livestock paths muddled the trail and I wove around trying to stay on the contour. I’d been sick for the night before our pre-dawn start, and last saw Nik and the porters mid-morning, six hours ago. After another hour, my legs buckled and I slumped down in the dirt. I considered the possibility that I might not find them before nightfall. The rocky peak was now in fuller view and I felt better about my general direction but exhausted and the valley continued to rise. I spotted a trail on the other side of the river, now far below, and my stomach tightened again. Maybe I’m on the wrong side. Waves of rage and disbelief engulfed me. How is this still happening? Where the hell is Nik?

I had a jacket and a few sips of water left. Keep moving while it’s still light.

[ls]

I know what had drawn me to Nik Berry as a person—he listens to you with wide-open eyes and has an easy, good-natured manner. In climbing, I respected his motivation, confidence and dedication to trying hard. Nik embraces 4 a.m. starts like the words that always come into my mind—a joyful robot. We’d hit it off in March, while working at a Red Rocks climbing event for our mutual sponsor Outdoor Research, when we squeezed in climbing whenever possible, early or late. We simul-climbed by headlamp, practiced our dance moves at cold belays, and unlocked sequences of difficult pitches.

When I rose yet again in the dark, climbing in Red Rocks for the fourth day in a row, I said to my girlfriend, “I think I’ve found someone more motivated than I am for a change.”

She just said, “It’s about time.”

Nik and I had each set our sights on Yosemite, and decided to climb a free route together on El Capitan. He arrived in the Valley before I did, free climbing The Prophet (VI, 5.13d R) and then hiking other climbers’ loads up Half Dome and El Cap for extra money before we two attempted El Corazon (VI 5.13b). On El Corazon he weathered my initial (and, I’m afraid, not entirely atypical) negativity when I previewed and first tried the top cruxes:

“I can’t do it,” I said. I also said, serially:

“I don’t get it.”

“My shoulder hurts.”

And: “That sequence won’t work/is too powerful for me.”

Nik was patient and said straightforward and odd but comical things like, “Too bad you don’t have a penis.” I saw a little brother in him, someone I could talk shit to and whose encouragement when so effusive when I was leading that my attention to trying hard increased. On run-out, and potentially dangerous sections of climbing, I learned to take his laughter as a sign that things were particularly dire. I wanted to learn to face my death smiling like I imagined he would one day.

You might think a guy in his mid-20s (Nik is 26) would be more likely to climb big projects with another young male rather than a 30-year-old woman—but we both like to bite off as big a goal as we think we can possibly chew and our awkward personalities/odd-ball natures felt largely compatible to me. I played into the big sister role with Nik and he seemed to appreciate that as well as my ambition and technical capability. Nik is such a strong climber—ridiculously cool-headed and durable—that I questioned my value in the partnership, because I was accustomed to bringing those same strengths to other partnerships. On El Corazon I felt worthy when I was able to unlock some crux sequences for both of us and I began to open to what I could offer and learn.

Nik didn’t need as much rest as I did, so on El Corazon I either had to keep up or ask him to slow down, and accepting a lead on the route was more a choice than a necessity. On our fourth day on El Corazon, the A5 traverse was my final [difficult] lead and I was solid.

Nik followed and I laughed as he whined in imitation [of my previous attempts at leading the traverse], “This is hard. I’m just gonna think negative thoughts.” At the anchor, he congratulated me with typical generosity: “That was sick. You remembered how to try hard.”

[ls]

I wanted to experience a mountain culture in Central Asia, and after a friend’s report from the previous season, became drawn to Kyrgyzstan’s stellar weather, scant snow, 3,000-foot walls and 4,500-foot ridgelines. Most of my big trips have been with partners after developing a long history of supporting one another’s highs and lows. I often felt a greater accountability in my partnerships with women, and thus the dynamics were all the more supportive as we helped each other push ourselves. While I still often seek out climbing with women, this year I was focused on pushing my climbing performance, and simply finding motivated partners whom I got along with well. In the Spring, I’d teamed up with a 23-yr old young gun, Brad Gobrite, and freed the Hallucinogen Wall (VI 5.13R) and enjoyed reconnecting with youthful enthusiasm that believes anything is possible.

I asked Nik if he’d be interested in freeing big walls the Karavshin region of Kyrgyzstan, we secured funding, and suddenly only five weeks remained before departure. Nik had traveled little outside of North America, and the pre-trip planning hurdles I shared with him were often met with the joke, “Why don’t we just go to the Bugaboos? I felt responsible for the logistical success of the trip and thus a bit protective of our organization from travel to obtaining area information to permits to hiring porters and base camp cooks. In truth I wanted Nik to share the planning responsibility but I wanted him to know what to do without telling him. I settled for requesting assistance on specific tasks and told myself that this big-sister leader role was a new growth area for me.

But I wanted an adventure and told myself that Nik did as well, even when he asked whether the hassles of getting halfway across the world with 400 pounds of gear “maybe” to go rock climbing were worth it.

I was confident in Nik’s and my ability to climb together, however found myself lecturing him about what it meant to climb in remote areas and to travel internationally.

“If we don’t have it, there’s no getting it,” I said. “We need to remember every necessary item. No popping back into town for an antibiotic.”

Nik and I hadn’t climbed in any isolated region together. Our risk thresholds had seemed close enough on El Cap, but overall I was more conservative, so I bugged him [chronically] about things like bringing a helmet.

Texting was our main mode of communication and in our final days of packing, messages such as, “Will you get more 3/8 bolts?” or “How much does your sleeping bag weigh?” zinged back and forth. The night before our flight, I sent Nik a text.

“We’re going to freaking Kyrgyzstan!!”

“Where the hell is that?” he responded. “Have fun out there.”

“Yeah, have you even looked at a map?” I asked.

“That’s what a pilot is for, silly,” he countered.

I found Nik at JFK airport, already $600 deep in excess baggage fees. I was relieved just by the sight of him: Now we were on the adventure together. We flew to Bishtek and, while waiting for lost bags to arrive, adjusted to the 12-hour time difference and explored a capital of bleak Soviet Bloc architecture: uniform, blocky gray concrete. Mostly, we sampled bazaar foods—farmers’ cheese, salty pickled cabbage and runny kefir yogurt—and tried not to get mugged. I laughed as Nik’s guileless gaze invited the attentions of peddler after peddler, but was dogmatic when he seemed too carefree.

“You can’t just leave your bags over there!” I scolded.

“I’m watching them,” he protested, but he retrieved the bags.

[ls]

Five days after our arrival, my gut unraveled, probably from the effects of bazaar food sitting out under a 100-degree sun.

The people from the guide service we’d hired had told us little of getting to base camp except that they’d arranged donkeys and porters for the day-and-a-half walk. After a short flight from Bishkek to the town of Batken, then a three-hour drive in a hired car past the Tajik border point of Vorukh, where the passable road ends, we reached the trailhead, stopping with our driver at a house beside the river. In the evening two Tajik porters arrived and began to load our bags onto the donkeys. I vomited and then tried to convey with gestures that I wasn’t fit to begin this evening. The older of the two porters looked disappointed but nodded as I pointed to my watch and suggested 5 a.m. “Ak Su,” he repeated, and I realized I’d agreed to complete the 30-mile walk in a day.

As others slept, I endured dizzying cycles of illness, stumbling around outside under a clear starry sky. At first light, I watched as the porters loaded our 400 pounds of equipment onto four donkeys—who gave little protest except to shit as the weighty contraptions were cinched across their bellies. In solidarity, my hollow stomach churned acid.

The porters, donkeys, Nik and I began at 5 a.m. A desert landscape stretched before us and I had less than a liter of water. The river was thick with sediment. Nik gave me most of his remaining water and said he would use our water-treatment pills, which he carried in his daypack. I shuffled beside the river along a trail of sand and rocks, determined to keep moving. After a late-morning break, Nik and the porters pulled ahead, out of sight. As the sun rose higher, my legs and arms burned dry and I hid under the brim of my hat.

Two hours passed. Where are you, Nik? Where are the porters and donkeys? I glanced at my watch and groaned. 1 p.m. and many hot hours ahead. Around a twist in the trail, a full water bottle sat squarely on a rock. I assumed it was from Nik and was at once thankful and cautious—the water was deep brown and the last time I saw Nik treat water he’d used half the recommended dose.

Drawn by the shade of a shrub, I lay down and curled up around my pack. Had pride kept me from asking Nik to walk with me? Why couldn’t he get it like my other partners would have?

I awoke to the sound of hooves and laughter, and sat up to greet a man with donkeys.

“Ruski? Kyrgeez?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. “Ak Su.”

I pointed up river, and he nodded, gesturing to himself and saying, “Lailak.” I took out a map with a 6-inch quadrant of this Karavshin region. Lailak appeared to be further up river than the turn-off for the Ak-Su valley. He extended an open hand. I stood up into the sun and handed over my pack.

“Rahmat,” I said.

He repeated a word until I mounted the donkey, already laden with bags. The man asked about water and I fished out the silty bottle. He shook his head and emptied it onto the ground. The scene was slow motion and captivating.

When the donkey grew tired and began to lag, I dismounted. My thirst returned with a vengeance. I dragged behind my new friend, then saw another patch of shade over the river by a rickety wooden bridge. I found a clear stream feeding into the river, filled my bottles, drank down cold untreated water, and caught up to find the man waiting beside a dilapidated stone-mud structure. He sat on a rock and gestured for me to join him. Sun-bleached animal skulls were placed along a few of the walls, and he prayed aloud and I sat quietly, trying to open myself to the moment.

Resuming the walk, we soon came to an intersection with one trail leading left off the main river. The man continued but I was fairly certain that this was the turn off toward the Ak Su valley. I stopped and pointed.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

He nodded and gave me my pack. I thanked him, and handed him a little money.

At 3:30 p.m. I turned toward the Ak-Su trail [tk what Ak Su trail? I don’t understand the Q] and saw a heart and arrow drawn in the sand. Thank you, Nik.

By early evening, I began to consider my options for spending the night out. I paused at roofless shepherd’s hut, but I continued walking, telling myself I could return to it if I had to.

At nightfall (8pm?) I saw people and a house, livestock drawn close for the night. A few men and a boy stood together, each with a staff in hand.

“Salam-alay-kem,” I said as I approached. From behind the men, a smiling girl peeked out.

“Have you seen two Tajik men and one American?” My fingers walked across my hand and I pointed to myself when I said American.

“Yes,” the youngest of the men said in English.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

“Yes, Ak Su.”

“How long?” I asked, really pushing his English. I pointed to my watch and made numbers with my fingers. One? Two hours? The man held up three fingers. I shook my head and looked at the ground. Then he brought his hands together and I understood that I was invited to stay.

A woman came out of the house and invited me inside. On a small blanket in the middle of the floor sat a pot of chai and plate of naan. The woman—whose name, I learned, was Rita—poured chai and broke bread for me and then rose to tend to a large pot over a fire. The rest of the family entered and we sat in a circle: four men, two women, two kids, a baby. The father poured chai and broke bread for the group. Bowls of borscht were brought out. We dipped naan in the clear fatty broth of cabbage, potato, carrot and a piece of mutton. The women cleared food away, and Rita unrolled blankets from the edges of the room and pointed to mine. I lay down and tears filled my eyes. I was safe, fed, cared for.

When I rose in the morning, my legs were shaky but I felt both restored and blessedly fortunate to have found this beautiful family. The sun was high and neither Nik nor the porters had returned for me. Partially in disbelief, I lingered through the morning.

After breakfast, I told the family I was leaving for Ak Su. I gave Rita money. She shook her head, but I pressed and she took it to her husband; they seemed pleased. The boy and girl walked with me up the trail from their house. At an intersection, the boy pointed straight ahead and said, “Ak Su.”

En route, I was stopped at a military outpost, encircled [tk is that OK] by a group of armed young men as I stood before them, produced my passport, and tried to answer their questions. Leaving there, I soon met our porters, returning empty-handed from the Ak Su base camp and nodding that Nik and the bags were up river yet. By mid-afternoon I smelled fire and dung. A shepherd emerged from a bivy cave and led me over to Nik, who sat up in his sleeping bag under another rock.

“Hi,” I said. Emotions welled up as I found a place to sit and at first I didn’t hear what he said.

“Are you OK? I’ve been so worried.”

“Well, I made it,” I said, wondering what the hell he was doing napping instead of looking for me.

Nik described his surprise and dismay when the porters kept going and picked up speed without me. His only options had been either to wait or to follow and keep an eye on our bags, which contained our money and his passport as well as all our gear, and he kept expecting that the porters would eventually stop. When it was clear to him that they weren’t waiting, he felt trapped—too far away to check on me while still being able to catch up with the men. Before nightfall Nik asked the porters to break camp, only a mile from the intended Ak Su base camp, in hopes that I would find them. He couldn’t sleep. In the morning the porters packed up and kept going to base camp, and he followed.

I listened to his story, nodded and tried to understand. Nik said he would never leave a partner again under any circumstance. I wondered how my own determination and pride as an athlete might have contributed to the situation. Mostly I didn’t want to feel anything, and needed sleep.

I just said, “This bivy sucks.”

“Really?”

He was surprised that I didn’t see its resemblance to the bivy cave where we’d stayed on top of El Cap, but I just wanted to find fault.

“There’s nowhere for me to sleep,” I said irritably.

Nik dug out a flatter spot for me under our “Salathé” cave. I crawled into my bag and woke in the evening, when two shepherds—brothers who lived in the area from May to September—invited us for dinner.

Stepping out from the cave, I took in the landscape for the first time. Our camp was dry, rocky earth peppered with shrubby trees with few flat spots for a tent. Up valley was the snowy, jagged peak Ptitsa that shared a border with Tajikistan. The river poured down towards us and on either side massive granite formations rose up from steep hillsides of scree and then larger talus. I knew the formations from a computer screen, ridges and walls featured with cracks and blank faces. Now staring at the peaks, my mind kept trying to underestimate the distance between myself and the summits.

[ls]

Perestroika means overcoming stagnation and this internationally known route was a fitting first climb after the approach fiasco. Nik and I shared leads up its 25 pitches, starting with a 1,000-foot splitter crack. I took a 5.11+ flaring bulge, and Nik led the last crux, a 5.12- thin corner. Cold and shivering, I turned us around 500 feet before the summit, with Nik reluctant but conceding. He just zipped up his jacket collar and said, in validation, “Well, at least it’s starting to snow.”

After a day’s rest we hiked back up the 1,000-foot talus to the Russian Tower with static ropes and aid gear to check out the Russian Shield on the main steep face. My intestinal distress had returned and I hiked painfully slowly, avoiding eye contact with Nik. By the second pitch, it was clear that this route was a grander undertaking than our 20 bolts, hand drill and psych level were going to muster. We retreated. That evening, I begin taking antibiotics and in the middle of the night, hurrying out to relieve myself, I managed to roll my ankle. As tears gathered in my eyes, I congratulated myself on reaching a new level in being perennially pathetic.

The next day we decided to prioritize my recovery and hike to our supplier’s main camp in the adjacent Kara Su Valley, a 3-hour walk away in my pathetic state. We arrived to a busy scene in the Kara Su. Stand-up dome tents, crates of food, grazing cows and people filled a verdant green meadow with a clear stream running through it. Between the Russian climbing teams, Japanese trekkers, a British group, the German man in his speedo, the Russian cooks and Kyrgyz shepards, I lost count after 30-people.

Victor, our cook, greeted us and assured me that a little little vodka can cure anything. I curled up in our tent and Nik brought tea and a plate of plain rice. For a couple days, we lazed around in the meadow between feeding times and I fondly named our plush camp “Kara Kush.” And as hoped, the antibiotics eradicate every living thing in my gut and our two American friends, Josh Finkelstein and Pete Fasoldt, who have been climbing in the region, returned from a 3-day traverse of the formations dividing the AK Su and Kara Su valleys (Pk 4810, 1000 Y.O.R.C, and Pk Kotina). A “little, little” celebratory vodka is drunk. Soon Nik and I were restless to return to the solitude and rising granite of the Ak Su and bounced with excitement as Victor packed us off with fresh vegetable, grains, sausages, cheese and candy.

Upon our return to our Salathe bivy cave we find that the shepherd Jappar has left Nik a traditional Kyrgyz felt hat as a gift. Nik donned the tall white and thoroughly impractical accessory proudly as he built a fire and cooked with our borrowed Jappar’s cast-iron wok at our Salathé home. We discussed our next objective and Nik asked if I was fit to climb. He added, “If climbing means only doing things in the sun so that you’re not cold, that’s fine.” Nik’s concern felt genuine, and I proclaimed that my general psych level was high and while my ankle was swollen and discolored I assured him that it was manageable.

With binoculars we scoped out La Fiamma, an A3 Italian line just right of Perestroika, and the next day we climbed back up the shoulder of the Russian Tower to the notch below the Perestroika splitter. Deciding to see how far we could get that day, we stretched a 70-meter pitch up Perestroika to an anchor. From there I traversed right into La Fiamma territory, led a runout moderate slab into a shallow corner, and looked up at a snaking seam with a pin hammered into the bottom. Our hammer and set of pins sat back with Nik at the belay.

I yelled down, “I’ll just give it a go with what I have.” The placements got smaller and the climbing harder, up to 5.12-, but the rock was clean and solid. I read a way up the flaring finger grooves, foot edges and smears, Nik cheered and I completed the pitch with a satisfied whoop.

The next two pitches were more moderate, 5.10 climbing on solid rock, and we had just enough rope to rappel and fix most of the route back down to the ground. After a 12-hour day, we returned to base camp with plans to push for the summit in the morning.

We began in harmony at 4 a.m., music blaring from the speakers and water boiling. We jugged back up to our high point, Nik’s lead. Soon he was 20 feet off the belay, making insecure moves with only a marginal, tiny TCU between him and the belay. He reached and clipped a quarter-inch bolt, and I relaxed, sort of. He chuckled. Thumb pressing and insecure foot smears allowed him to move left, and he clipped another quarter-inch bolt. The final crux move ended with a sideways downward lunge to a flat jug. Solid marbled rock through a bulge completed this run-out 5.12c.

A dihedral rose above us, and to avoid placing bolts Nik built an awkward belay on a crumbly ledge midway up it. I began a difficult section, struggling to find satisfactory gear, and climbed up and down several times, unwilling to commit to a move into a thin and wet corner. I bitched and said Nik should take over the pitch (which would turn out to be 5.12-), but I didn’t come down.

Eventually I found enough gear to keep me off the ledge. I committed and found the climbing physical and insecure as I largely avoided the wet finger locks and relied on stemming. I shouted which helped me focus on trying hard and Nik cheered.

We merged with Perestroika from here, right where we had bailed the previous week. The temps were chilly but tolerable and this time I, too, wanted the summit. Five hundred feet of moderate splitters and corners led us to the top. We scrambled up summit choss and took in a sky of purples and pinks in the fading light, the FFA of the route behind us.

“That was a once-in-a-lifetime,” Nik said. “Anything else here is bonus.”

Our team morale was still high when we returned to camp after midnight.

After two rest days we racked up for a king line: Sugar Daddy (VI 5.11+), a ridgeline up the 4,507-meter Peak One Thousand Years of Russian Christianity. A splitter headwall proudly guarded the summit. We’d heard from Russians in the Kara Su that the route probably hadn’t been climbed in a day. We strategized for a hugely aerobic effort with roughly 5,000 feet of vertical gain and an unknown descent, and scoped a descent down the Northwest Ridge, a popular 5.10 that we’d heard can take 12 hours to rap.

The alarm sounded at 3:30 a.m. We hadn’t been to the base of the route, and so after hiking uphill for an hour we were as high as we could go in the dark, and waited for the sun. At the base, Nik considered his helmet before stuffing it back in his pack. Done with nagging, I said nothing.

In two hours, we simuled up the initial section and gained the lower-angle part of the ridge. We un-roped and straddled, scooted, huffed and puffed up it, and after about 1000 feet roped up again. The third, steeper section of the ridge took the longest, with inobvious route finding and technical cruxes. Nik was the hero, forging all the way through this block, dragging the entire rope behind him, and I simply cleaned the occasional cam. We topped out at 5 p.m., 10 hours after we began at the base, and hung out for 45 minutes on top, soaking up the sun before summoning the fortitude to return to the shade.

I volunteered to lead all the rappels. The pulls went smoothly, pitch by pitch, and we settled into a routine. While we still had light I tried to keep a sense of the general direction we wanted to head. By less than halfway down, I finished the last of my food and Nik unhesitatingly gave me some of his.

By 2 a.m. the situation had deteriorated. We’d been off the established rappels since before midnight and were just trying to get down by any safe means. Out of rappel cord, I cut into our lead rope, slinging flakes to descend. As I rapped into a cold small alcove and ledge, the slab below me dropped off into darkness. It was wet and I couldn’t find anything to anchor. I lowered farther. Cold water ran down the rope, a crack opened up into a chimney and I reached the end of the ropes without finding any anchor. I returned to the stance and searched again. My foot slipped and my hand splatted into icy water. Nik was 100 feet up at our last anchor.

“There’s nothing to sling!” I yelled.

“Isn’t there anything? Leave whatever. Cams, Stoppers… I don’t care.”

“I don’t know what to do!”

“Just do something!”

I slung a large rock, using a lot of our rope. After a few more rappels we were walking and Nik was hopeful enough to take off his harness. But soon a new dark abyss opened below our feet, and we began slinging and lowering yet again.

After rappelling from a slung rock down over a broken, overhanging amphitheater, I re-ascended the rope and insisted we stop until daylight. I was too tired to move, and stayed attached to the anchor, half sleeping between the cold and sliding and righting myself on the hillside.

When I awoke it was light and I was alone.

“Nik?” I shouted.

Nothing. I untangled myself from the rope and sprang to my feet.

“Nik!” I screamed. Nothing. “What the fuck!?”

My heart was racing. I began to run up the hill. Then I saw him, a mere 10 feet above, passed out on a flat spot of dirt and oblivious to my cries. He’d been there all along.

Madaleine Sorkin of Boulder has made several first and early ascents of 5.12/5.13 Grade VI walls, often in female teams. She recently earned a Master’s degree in Environmental and Land Use at the University of Colorado Denver. She and Nik Berry of Salt Lake climbed 4 routes during their trip to the Karavsdhin Region of Krygyzstan.

• La Fiamma (VI 5.12c R), Pik Slesova (Russian Tower 4240 m). Completed the first free ascent of the Italian aid line rated A3. Completed ground up, onsight with Nik Berry. Climbed over 1 ½ days.

• SugarDaddy, Pik 1000 Years of Russian Christianity(4507 m). Completed first single day ascent of 1500 m line (VI 5.11+).

• Perestroika (VI 5.12-), Pik Slesova

• The Alperin (V 5.10) Pk Asan

Tangled Borders

Partnership and Adventure in the Ak Su, Kyrgyzstan

By Madaleine Sorkin

The trail forked again at a shady grove of trees and I looked around, at first hopeful and then in frustration, for one of Nik’s arrows drawn in the sand. The junction was too large and vague to know where he may have drawn it. My throat and stomach clenched again and I closed my eyes to tears. This was still really happening I was still alone, in Kyrgyzstan of all places, and we hadn’t even climbed yet. The top of a rocky peak had come into view and I guessed the direction of the Ak Su valley, up a steepening valley of short grasses, shrubs and rocky soil. The rising trail baked under the late afternoon sun and a bright blue sky. I lingered under the grove reluctant to leave the companionship of the river. A small side spring into it had provided the only clearer water I’d had all day and its constant sound quieted my dark thoughts. One foot in front of the other, I repeated to myself but I felt heavier with each step. A headache split my right eye and my neck stiffened around a pain shooting up into my head. Where are they? Have they gone ahead to base camp? Surely someone will come back for me once they unload.

Livestock paths muddled the trail and I wove around trying to stay on the contour. I’d been sick for the night before our pre-dawn start, and last saw Nik and the porters mid-morning, six hours ago. After another hour, my legs buckled and I slumped down in the dirt. I considered the possibility that I might not find them before nightfall. The rocky peak was now in fuller view and I felt better about my general direction but exhausted and the valley continued to rise. I spotted a trail on the other side of the river, now far below, and my stomach tightened again. Maybe I’m on the wrong side. Waves of rage and disbelief engulfed me. How is this still happening? Where the hell is Nik?

I had a jacket and a few sips of water left. Keep moving while it’s still light.

[ls]

I know what had drawn me to Nik Berry as a person—he listens to you with wide-open eyes and has an easy, good-natured manner. In climbing, I respected his motivation, confidence and dedication to trying hard. Nik embraces 4 a.m. starts like the words that always come into my mind—a joyful robot. We’d hit it off in March, while working at a Red Rocks climbing event for our mutual sponsor Outdoor Research, when we squeezed in climbing whenever possible, early or late. We simul-climbed by headlamp, practiced our dance moves at cold belays, and unlocked sequences of difficult pitches.

When I rose yet again in the dark, climbing in Red Rocks for the fourth day in a row, I said to my girlfriend, “I think I’ve found someone more motivated than I am for a change.”

She just said, “It’s about time.”

Nik and I had each set our sights on Yosemite, and decided to climb a free route together on El Capitan. He arrived in the Valley before I did, free climbing The Prophet (VI, 5.13d R) and then hiking other climbers’ loads up Half Dome and El Cap for extra money before we two attempted El Corazon (VI 5.13b). On El Corazon he weathered my initial (and, I’m afraid, not entirely atypical) negativity when I previewed and first tried the top cruxes:

“I can’t do it,” I said. I also said, serially:

“I don’t get it.”

“My shoulder hurts.”

And: “That sequence won’t work/is too powerful for me.”

Nik was patient and said straightforward and odd but comical things like, “Too bad you don’t have a penis.” I saw a little brother in him, someone I could talk shit to and whose encouragement when so effusive when I was leading that my attention to trying hard increased. On run-out, and potentially dangerous sections of climbing, I learned to take his laughter as a sign that things were particularly dire. I wanted to learn to face my death smiling like I imagined he would one day.

You might think a guy in his mid-20s (Nik is 26) would be more likely to climb big projects with another young male rather than a 30-year-old woman—but we both like to bite off as big a goal as we think we can possibly chew and our awkward personalities/odd-ball natures felt largely compatible to me. I played into the big sister role with Nik and he seemed to appreciate that as well as my ambition and technical capability. Nik is such a strong climber—ridiculously cool-headed and durable—that I questioned my value in the partnership, because I was accustomed to bringing those same strengths to other partnerships. On El Corazon I felt worthy when I was able to unlock some crux sequences for both of us and I began to open to what I could offer and learn.

Nik didn’t need as much rest as I did, so on El Corazon I either had to keep up or ask him to slow down, and accepting a lead on the route was more a choice than a necessity. On our fourth day on El Corazon, the A5 traverse was my final [difficult] lead and I was solid.

Nik followed and I laughed as he whined in imitation [of my previous attempts at leading the traverse], “This is hard. I’m just gonna think negative thoughts.” At the anchor, he congratulated me with typical generosity: “That was sick. You remembered how to try hard.”

[ls]

I wanted to experience a mountain culture in Central Asia, and after a friend’s report from the previous season, became drawn to Kyrgyzstan’s stellar weather, scant snow, 3,000-foot walls and 4,500-foot ridgelines. Most of my big trips have been with partners after developing a long history of supporting one another’s highs and lows. I often felt a greater accountability in my partnerships with women, and thus the dynamics were all the more supportive as we helped each other push ourselves. While I still often seek out climbing with women, this year I was focused on pushing my climbing performance, and simply finding motivated partners whom I got along with well. In the Spring, I’d teamed up with a 23-yr old young gun, Brad Gobrite, and freed the Hallucinogen Wall (VI 5.13R) and enjoyed reconnecting with youthful enthusiasm that believes anything is possible.

I asked Nik if he’d be interested in freeing big walls the Karavshin region of Kyrgyzstan, we secured funding, and suddenly only five weeks remained before departure. Nik had traveled little outside of North America, and the pre-trip planning hurdles I shared with him were often met with the joke, “Why don’t we just go to the Bugaboos? I felt responsible for the logistical success of the trip and thus a bit protective of our organization from travel to obtaining area information to permits to hiring porters and base camp cooks. In truth I wanted Nik to share the planning responsibility but I wanted him to know what to do without telling him. I settled for requesting assistance on specific tasks and told myself that this big-sister leader role was a new growth area for me.

But I wanted an adventure and told myself that Nik did as well, even when he asked whether the hassles of getting halfway across the world with 400 pounds of gear “maybe” to go rock climbing were worth it.

I was confident in Nik’s and my ability to climb together, however found myself lecturing him about what it meant to climb in remote areas and to travel internationally.

“If we don’t have it, there’s no getting it,” I said. “We need to remember every necessary item. No popping back into town for an antibiotic.”

Nik and I hadn’t climbed in any isolated region together. Our risk thresholds had seemed close enough on El Cap, but overall I was more conservative, so I bugged him [chronically] about things like bringing a helmet.

Texting was our main mode of communication and in our final days of packing, messages such as, “Will you get more 3/8 bolts?” or “How much does your sleeping bag weigh?” zinged back and forth. The night before our flight, I sent Nik a text.

“We’re going to freaking Kyrgyzstan!!”

“Where the hell is that?” he responded. “Have fun out there.”

“Yeah, have you even looked at a map?” I asked.

“That’s what a pilot is for, silly,” he countered.

I found Nik at JFK airport, already $600 deep in excess baggage fees. I was relieved just by the sight of him: Now we were on the adventure together. We flew to Bishtek and, while waiting for lost bags to arrive, adjusted to the 12-hour time difference and explored a capital of bleak Soviet Bloc architecture: uniform, blocky gray concrete. Mostly, we sampled bazaar foods—farmers’ cheese, salty pickled cabbage and runny kefir yogurt—and tried not to get mugged. I laughed as Nik’s guileless gaze invited the attentions of peddler after peddler, but was dogmatic when he seemed too carefree.

“You can’t just leave your bags over there!” I scolded.

“I’m watching them,” he protested, but he retrieved the bags.

[ls]

Five days after our arrival, my gut unraveled, probably from the effects of bazaar food sitting out under a 100-degree sun.

The people from the guide service we’d hired had told us little of getting to base camp except that they’d arranged donkeys and porters for the day-and-a-half walk. After a short flight from Bishkek to the town of Batken, then a three-hour drive in a hired car past the Tajik border point of Vorukh, where the passable road ends, we reached the trailhead, stopping with our driver at a house beside the river. In the evening two Tajik porters arrived and began to load our bags onto the donkeys. I vomited and then tried to convey with gestures that I wasn’t fit to begin this evening. The older of the two porters looked disappointed but nodded as I pointed to my watch and suggested 5 a.m. “Ak Su,” he repeated, and I realized I’d agreed to complete the 30-mile walk in a day.

As others slept, I endured dizzying cycles of illness, stumbling around outside under a clear starry sky. At first light, I watched as the porters loaded our 400 pounds of equipment onto four donkeys—who gave little protest except to shit as the weighty contraptions were cinched across their bellies. In solidarity, my hollow stomach churned acid.

The porters, donkeys, Nik and I began at 5 a.m. A desert landscape stretched before us and I had less than a liter of water. The river was thick with sediment. Nik gave me most of his remaining water and said he would use our water-treatment pills, which he carried in his daypack. I shuffled beside the river along a trail of sand and rocks, determined to keep moving. After a late-morning break, Nik and the porters pulled ahead, out of sight. As the sun rose higher, my legs and arms burned dry and I hid under the brim of my hat.

Two hours passed. Where are you, Nik? Where are the porters and donkeys? I glanced at my watch and groaned. 1 p.m. and many hot hours ahead. Around a twist in the trail, a full water bottle sat squarely on a rock. I assumed it was from Nik and was at once thankful and cautious—the water was deep brown and the last time I saw Nik treat water he’d used half the recommended dose.

Drawn by the shade of a shrub, I lay down and curled up around my pack. Had pride kept me from asking Nik to walk with me? Why couldn’t he get it like my other partners would have?

I awoke to the sound of hooves and laughter, and sat up to greet a man with donkeys.

“Ruski? Kyrgeez?” he asked.

“No,” I replied. “Ak Su.”

I pointed up river, and he nodded, gesturing to himself and saying, “Lailak.” I took out a map with a 6-inch quadrant of this Karavshin region. Lailak appeared to be further up river than the turn-off for the Ak-Su valley. He extended an open hand. I stood up into the sun and handed over my pack.

“Rahmat,” I said.

He repeated a word until I mounted the donkey, already laden with bags. The man asked about water and I fished out the silty bottle. He shook his head and emptied it onto the ground. The scene was slow motion and captivating.

When the donkey grew tired and began to lag, I dismounted. My thirst returned with a vengeance. I dragged behind my new friend, then saw another patch of shade over the river by a rickety wooden bridge. I found a clear stream feeding into the river, filled my bottles, drank down cold untreated water, and caught up to find the man waiting beside a dilapidated stone-mud structure. He sat on a rock and gestured for me to join him. Sun-bleached animal skulls were placed along a few of the walls, and he prayed aloud and I sat quietly, trying to open myself to the moment.

Resuming the walk, we soon came to an intersection with one trail leading left off the main river. The man continued but I was fairly certain that this was the turn off toward the Ak Su valley. I stopped and pointed.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

He nodded and gave me my pack. I thanked him, and handed him a little money.

At 3:30 p.m. I turned toward the Ak-Su trail [tk what Ak Su trail? I don’t understand the Q] and saw a heart and arrow drawn in the sand. Thank you, Nik.

By early evening, I began to consider my options for spending the night out. I paused at roofless shepherd’s hut, but I continued walking, telling myself I could return to it if I had to.

At nightfall (8pm?) I saw people and a house, livestock drawn close for the night. A few men and a boy stood together, each with a staff in hand.

“Salam-alay-kem,” I said as I approached. From behind the men, a smiling girl peeked out.

“Have you seen two Tajik men and one American?” My fingers walked across my hand and I pointed to myself when I said American.

“Yes,” the youngest of the men said in English.

“Ak Su?” I asked.

“Yes, Ak Su.”

“How long?” I asked, really pushing his English. I pointed to my watch and made numbers with my fingers. One? Two hours? The man held up three fingers. I shook my head and looked at the ground. Then he brought his hands together and I understood that I was invited to stay.

A woman came out of the house and invited me inside. On a small blanket in the middle of the floor sat a pot of chai and plate of naan. The woman—whose name, I learned, was Rita—poured chai and broke bread for me and then rose to tend to a large pot over a fire. The rest of the family entered and we sat in a circle: four men, two women, two kids, a baby. The father poured chai and broke bread for the group. Bowls of borscht were brought out. We dipped naan in the clear fatty broth of cabbage, potato, carrot and a piece of mutton. The women cleared food away, and Rita unrolled blankets from the edges of the room and pointed to mine. I lay down and tears filled my eyes. I was safe, fed, cared for.

When I rose in the morning, my legs were shaky but I felt both restored and blessedly fortunate to have found this beautiful family. The sun was high and neither Nik nor the porters had returned for me. Partially in disbelief, I lingered through the morning.

After breakfast, I told the family I was leaving for Ak Su. I gave Rita money. She shook her head, but I pressed and she took it to her husband; they seemed pleased. The boy and girl walked with me up the trail from their house. At an intersection, the boy pointed straight ahead and said, “Ak Su.”

En route, I was stopped at a military outpost, encircled [tk is that OK] by a group of armed young men as I stood before them, produced my passport, and tried to answer their questions. Leaving there, I soon met our porters, returning empty-handed from the Ak Su base camp and nodding that Nik and the bags were up river yet. By mid-afternoon I smelled fire and dung. A shepherd emerged from a bivy cave and led me over to Nik, who sat up in his sleeping bag under another rock.

“Hi,” I said. Emotions welled up as I found a place to sit and at first I didn’t hear what he said.

“Are you OK? I’ve been so worried.”

“Well, I made it,” I said, wondering what the hell he was doing napping instead of looking for me.

Nik described his surprise and dismay when the porters kept going and picked up speed without me. His only options had been either to wait or to follow and keep an eye on our bags, which contained our money and his passport as well as all our gear, and he kept expecting that the porters would eventually stop. When it was clear to him that they weren’t waiting, he felt trapped—too far away to check on me while still being able to catch up with the men. Before nightfall Nik asked the porters to break camp, only a mile from the intended Ak Su base camp, in hopes that I would find them. He couldn’t sleep. In the morning the porters packed up and kept going to base camp, and he followed.

I listened to his story, nodded and tried to understand. Nik said he would never leave a partner again under any circumstance. I wondered how my own determination and pride as an athlete might have contributed to the situation. Mostly I didn’t want to feel anything, and needed sleep.

I just said, “This bivy sucks.”

“Really?”

He was surprised that I didn’t see its resemblance to the bivy cave where we’d stayed on top of El Cap, but I just wanted to find fault.

“There’s nowhere for me to sleep,” I said irritably.

Nik dug out a flatter spot for me under our “Salathé” cave. I crawled into my bag and woke in the evening, when two shepherds—brothers who lived in the area from May to September—invited us for dinner.

Stepping out from the cave, I took in the landscape for the first time. Our camp was dry, rocky earth peppered with shrubby trees with few flat spots for a tent. Up valley was the snowy, jagged peak Ptitsa that shared a border with Tajikistan. The river poured down towards us and on either side massive granite formations rose up from steep hillsides of scree and then larger talus. I knew the formations from a computer screen, ridges and walls featured with cracks and blank faces. Now staring at the peaks, my mind kept trying to underestimate the distance between myself and the summits.

[ls]

Perestroika means overcoming stagnation and this internationally known route was a fitting first climb after the approach fiasco. Nik and I shared leads up its 25 pitches, starting with a 1,000-foot splitter crack. I took a 5.11+ flaring bulge, and Nik led the last crux, a 5.12- thin corner. Cold and shivering, I turned us around 500 feet before the summit, with Nik reluctant but conceding. He just zipped up his jacket collar and said, in validation, “Well, at least it’s starting to snow.”

After a day’s rest we hiked back up the 1,000-foot talus to the Russian Tower with static ropes and aid gear to check out the Russian Shield on the main steep face. My intestinal distress had returned and I hiked painfully slowly, avoiding eye contact with Nik. By the second pitch, it was clear that this route was a grander undertaking than our 20 bolts, hand drill and psych level were going to muster. We retreated. That evening, I begin taking antibiotics and in the middle of the night, hurrying out to relieve myself, I managed to roll my ankle. As tears gathered in my eyes, I congratulated myself on reaching a new level in being perennially pathetic.

The next day we decided to prioritize my recovery and hike to our supplier’s main camp in the adjacent Kara Su Valley, a 3-hour walk away in my pathetic state. We arrived to a busy scene in the Kara Su. Stand-up dome tents, crates of food, grazing cows and people filled a verdant green meadow with a clear stream running through it. Between the Russian climbing teams, Japanese trekkers, a British group, the German man in his speedo, the Russian cooks and Kyrgyz shepards, I lost count after 30-people.

Victor, our cook, greeted us and assured me that a little little vodka can cure anything. I curled up in our tent and Nik brought tea and a plate of plain rice. For a couple days, we lazed around in the meadow between feeding times and I fondly named our plush camp “Kara Kush.” And as hoped, the antibiotics eradicate every living thing in my gut and our two American friends, Josh Finkelstein and Pete Fasoldt, who have been climbing in the region, returned from a 3-day traverse of the formations dividing the AK Su and Kara Su valleys (Pk 4810, 1000 Y.O.R.C, and Pk Kotina). A “little, little” celebratory vodka is drunk. Soon Nik and I were restless to return to the solitude and rising granite of the Ak Su and bounced with excitement as Victor packed us off with fresh vegetable, grains, sausages, cheese and candy.

Upon our return to our Salathe bivy cave we find that the shepherd Jappar has left Nik a traditional Kyrgyz felt hat as a gift. Nik donned the tall white and thoroughly impractical accessory proudly as he built a fire and cooked with our borrowed Jappar’s cast-iron wok at our Salathé home. We discussed our next objective and Nik asked if I was fit to climb. He added, “If climbing means only doing things in the sun so that you’re not cold, that’s fine.” Nik’s concern felt genuine, and I proclaimed that my general psych level was high and while my ankle was swollen and discolored I assured him that it was manageable.

With binoculars we scoped out La Fiamma, an A3 Italian line just right of Perestroika, and the next day we climbed back up the shoulder of the Russian Tower to the notch below the Perestroika splitter. Deciding to see how far we could get that day, we stretched a 70-meter pitch up Perestroika to an anchor. From there I traversed right into La Fiamma territory, led a runout moderate slab into a shallow corner, and looked up at a snaking seam with a pin hammered into the bottom. Our hammer and set of pins sat back with Nik at the belay.

I yelled down, “I’ll just give it a go with what I have.” The placements got smaller and the climbing harder, up to 5.12-, but the rock was clean and solid. I read a way up the flaring finger grooves, foot edges and smears, Nik cheered and I completed the pitch with a satisfied whoop.

The next two pitches were more moderate, 5.10 climbing on solid rock, and we had just enough rope to rappel and fix most of the route back down to the ground. After a 12-hour day, we returned to base camp with plans to push for the summit in the morning.

We began in harmony at 4 a.m., music blaring from the speakers and water boiling. We jugged back up to our high point, Nik’s lead. Soon he was 20 feet off the belay, making insecure moves with only a marginal, tiny TCU between him and the belay. He reached and clipped a quarter-inch bolt, and I relaxed, sort of. He chuckled. Thumb pressing and insecure foot smears allowed him to move left, and he clipped another quarter-inch bolt. The final crux move ended with a sideways downward lunge to a flat jug. Solid marbled rock through a bulge completed this run-out 5.12c.